I’m genuinely elated to announce this Monday, March 25th, 2024 the release of Greco-Mormon, a new chapbook under my fresh pen name August Janson. In its 43 pages are 12 poems written and edited over eight years, divided into two parts, with two longer sequences of seven and 10 poems respectively. The edition’s run will be 250, my largest self-produced printing to date. Orders will be fulfilled on-demand with the first 50 copies in a hand-stitched binding.

Greco-Mormon can be published in my Ko-fi store here for $10 (postage included)

My intention below is to give some personal and historical context to Greco-Mormon. Like a book’s version of special features, this isn’t necessary for an appreciation of the poems individually or the collection as a whole, but rather to serve a scant purpose for the critically curious, however long the coherence of the Internet lasts and while there are potential readers of American poetry with an eye on the present and an eye on the past.

Why the pen name August Janson: A brief genealogy

Although I no longer practice the faith I grew up in, when dug up and exposed to the stark sunlight of the Great Basin, my religious roots reveal them to be fifth generation Mormon. I was in the church from birth to 18 – technically from 8, the age of baptism and confirmation in the LDS church. I’ve never rescinded my membership and have walked other paths of practice since 18, but although I’ve lived longer not attending the church of my ancestors than attending, the resonance of its teachings, hymns, beliefs, customs, and the whole octave of its paradoxical culture still rings in my ears. To turn down the volume, I needed to distance myself by giving the poetic voice of these poems a new name – though, not entirely new.

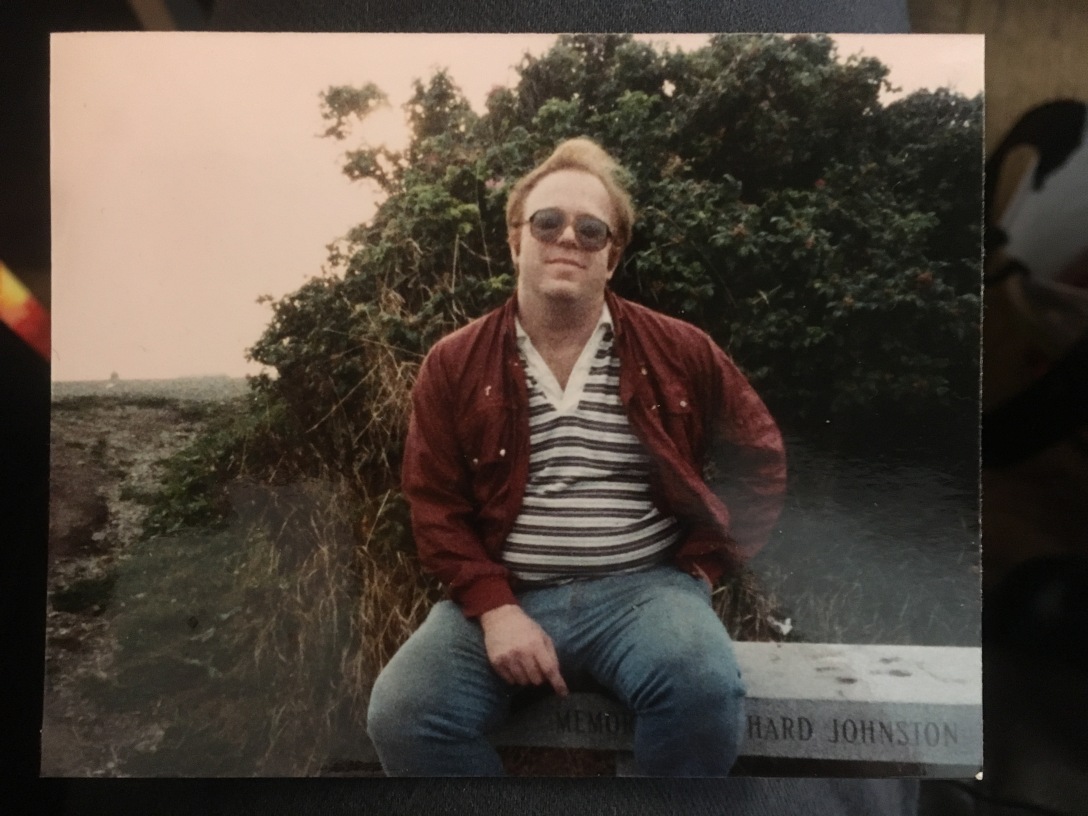

I was born with the last name Janson. It was given to me by my biological father Phillip John Janson, who recently died in August 2023, and was preceded in death by my adoptive father Bob (who gave me his adopted surname, Burns, in 1990), and my stepfather Charlie, all to whom I dedicate the chapbook. The Jansons I descend from on Phillip’s side are Jansons of Sweden’s Stockholm and Uppsala Counties, rather than Jansons from Britain, Ireland, France, or Germany (see this 23andMe page for the commonality of the surname). Phillip’s father, my grandfather Alonzo (“Lonnie”) Delmar Janson was the grandson of Frans Gustaf Janson, whose journey to the land of Deseret began with the informal visits and home teachings by Mormon missionaries, in fact, the first elders sent abroad to the non-English speaking countries of Scandinavia.

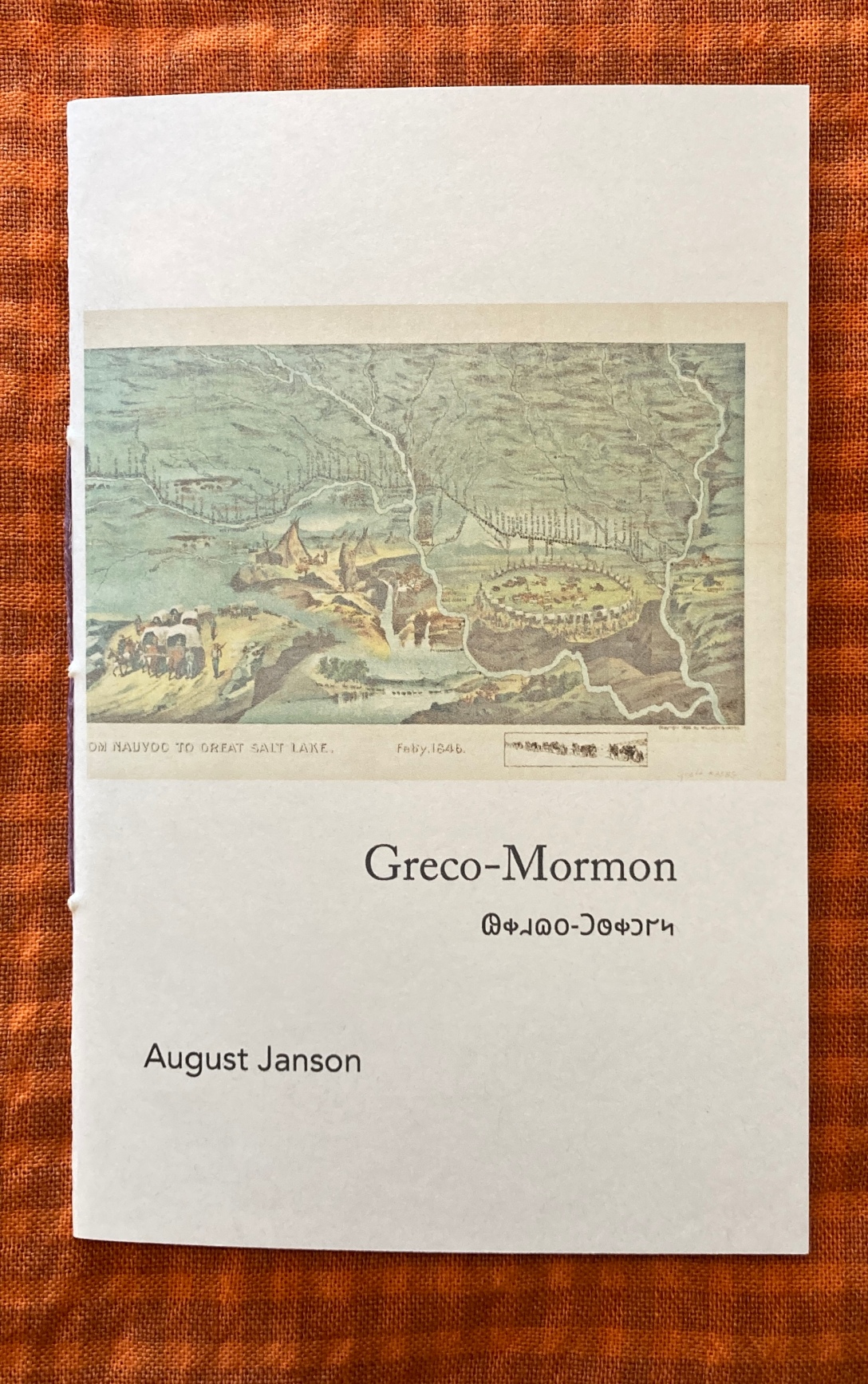

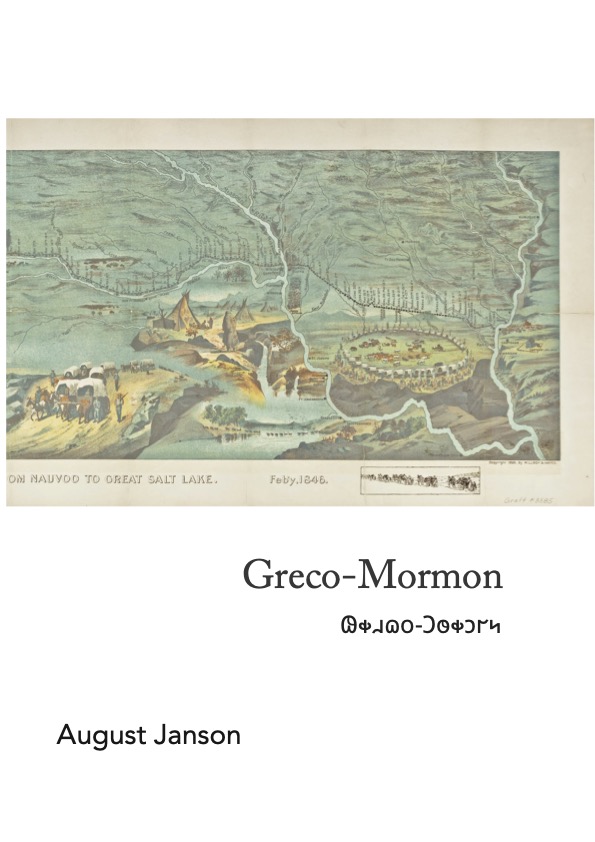

The front cover of the chapbook with explanatory notes

The cover of Greco-Mormon, with a digital clipping of the route taken by Mormon pioneers from Nauvoo, Illinois to the Salt Lake Valley in Utah Territory in the winter of 1846, later known as the Mormon Trail.

The script below the title is the same in the phonetic alphabet Deseret (a term meaning “honeybee”) that was developed in 1854 by George D. Watt, the first English convert to the LDS church, at the behest of the second prophet and president of the church, Brigham Young.

The purpose of developing the alphabet was both theocratic and functional. Before statehood, Young was the leader of both the church and the State of Deseret, and the script served as a means of helping converts quickly learn English phonemes from non-English speaking countries – initially, from my ancestors in Scandinavia (Source: http://deseretalphabet.org/)

In the mid-to-late nineteenth century, Sweden had only just ceased enforcing religious laws of compulsory (Lutheran) church attendance, laws against religious conversion, and laws barring emigration. The first part of my pen name, August, is in honor of Maria Augusta Carlsson who married great-great-grandfather Frans. She had also converted to the early LDS church in Sweden and left her family to emigrate to the US to help “build the kingdom.” This is quite a historical irony, as Swedish converts who crossed the Atlantic and followed the Mormon Trail to the American West were leaving a native country that was gradually democratizing and pulling apart church and state – only to arrive in the theocratic bastion of Utah Territory where both were the same.

If Frans Gustaf and Maria Augusta hadn’t chosen to take their individual leaps of faith across an ocean, they wouldn’t have met one another across their adjacent hotel rooms in New York City in late September 1875, beginning a patriarchal sequence of marriages and birthings that produced me 110 years later. My Mormon and American story begins earliest with them, and so August Janson is both the subjective double and poetic object of Greco-Mormon.

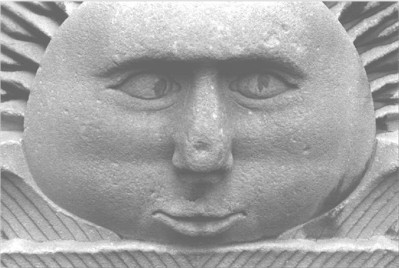

The frontispiece to Greco-Mormon: Detail of carved sunstone relief sculpture from the original Nauvoo Temple (1841-1846) before its abandonment due to religious intolerance and destruction by arsonists (Source: https://history.churchofjesuschrist.org/content/museum/museum-treasures-nauvoo-temple-in-ruins-lithograph?lang=eng).

Greco-Mormon can be published in my Ko-fi store here for $10 (postage included)

The title of the chapbook: Mythopoesis and history

Yes, it’s a cheap and punny chapbook title that reminds you of school – so the following brief lesson by me, a certified teacher, has the historical and anecdotal information you’ll need to understand for the Greco-Mormon quiz you can unlock with the enclosed code you’ll receive after purchase of the chapbook (sarcasm detected):

The Greco-Roman period was short, close to the same amount of time between my great-great-grandparents and me (116 years – approximately how long it took the LDS church to get to its first million members). The Achaean League, the last alliance of Greek city-states, was dissolved by the Roman Republic after the Battle of Corinth in 146 BCE, marking the official end of Grecian sovereignty, as well as the tapering off of Hellenistic art and culture. The Greco-Roman period is usually demarcated at 30 BCE with the absorption of Ptolemaic Egypt and the establishment of the Roman Empire by Octavian. Technically speaking, the Greek peoples never again ruled over themselves until the Greek War for Independence in 1821, the year when Joseph Smith first claimed his theophanic vision occurred (there are multiple versions, suggesting a sculpted narrative by Smith).

The Romans absorbed the lands and peoples of the Greeks but had also for the previous centuries been grafting the wisdom of Greek philosophers and their styles and techniques in the plastic and performative arts. This further differentiated them from their native Etruscan ancestors in the Apennine Peninsula, and if we subscribe to Virgil’s Aeneid as being more than mythopoeic nation-building, taking some truth in the origin of Rome with an Aeneas-like figure with errant Trojans [read: Anatolians] ending up along the Tiber, another instance of “Latin” cultural diffusion. I would argue that the Aeneid can be read as a precursor myth of Western expansion, with a people fleeing a city of destruction and journeying through the wilderness (of the Mediterranean Sea) to a new home – the same story at the root of the settling of Deseret and by my Mormon ancestors. End of lesson.

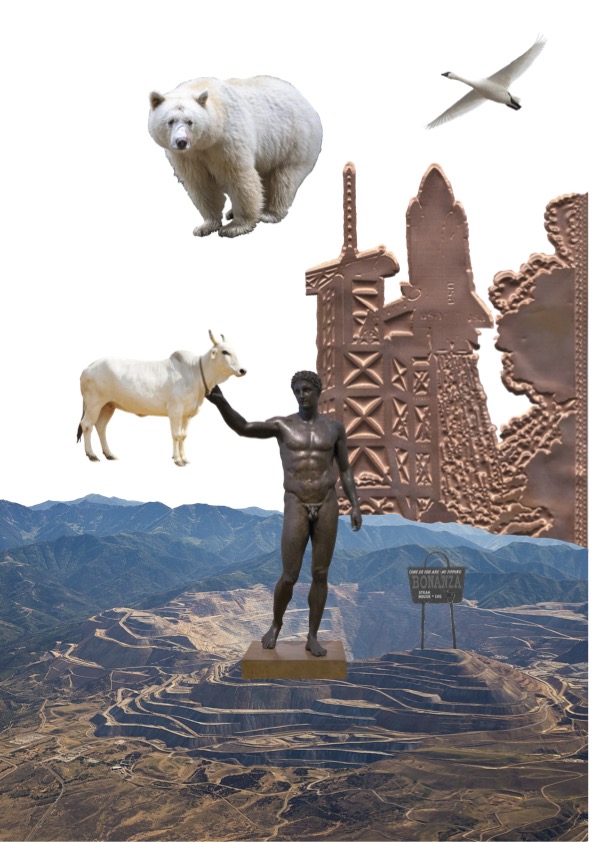

The back cover of the chapbook with a key to its constituent parts

- Center-right: Scan of a copper postcard of a space shuttle launch, made using copper mined in the Salt Lake Valley at Bingham Canyon (pictured at bottom), the largest man-made excavation on Earth

- In an arc: Three animals representing prominent Northern constellations: Taurus, Ursa Major, and Cygnus – one tamed, one wild, one free

- Center: The Antikythera Ephebe statue, found in a Greco-Roman shipwreck in 1900, most likely sculpted by Euphranor of Corinth in the 4th century BC, which I’ve made to look like he’s “taming the ox” of the heavens, though it’s believed he actually held a sphere – perhaps a golden apple

- Right: Clipping of a road sign in Texas for the Bonanza steakhouse, where my adoptive father Bob worked during high school, started by Dan Blocker, a TV actor from the show Bonanza (1959-1973), set during the era of Mormon migration and Western expansion

Extra-credit. A salient point that should affect the reading of my poems hinges around the testimony of members of the LDS church in the truth of The Book of Mormon as another testament of Jesus Christ, but more specifically, a factual historical record of the Ancient Americas. That history begins in the Middle East with a lost tribe of Israel led by the patriarch Lehi out of Jerusalem before it fell to Nebuchadnezzar. They then traversed the Atlantic to the Americas where they established a Judaic/Christ-anticipating (not exactly Messianic) religious civilization, like a Christian Aeneas or a New World Noah.

Regardless of one’s testimony, the archaeological record does not provide any abundance of hard evidence of such an origin story of the American people. The genetics of indigenous peoples who migrated to America across Beringia reveal Northern Asiatic origins between 25-10,000 BCE, not Middle-Eastern Semitic from the 6th century BCE. Technologically, the first peoples advanced enough of whom we actually have evidence of traversing the Atlantic to America are, in fact, 11th-century Scandinavians. Mediterranean vessels for many, many centuries before and after Lehi’s time had much too shallow of a freeboard (the distance from the waterline to the upper deck level) for transoceanic travel. Although according to The Book of Mormon, as with Noah in Genesis, Lehi was shown a way by God. For the true believer, the matter is one of faith, not fact.

In 1087, around thirty years after the latest carbon dating at the L’Anse aux Meadows site, the temple was burned down by Sweden’s first Christian king, Inge the Elder.

Unfortunately, the fact of the discovery of the Scandinavian settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland has been hijacked as grounds for a land claim to all of North America by white nationalists of this continent, and as a further means of justifying arguments and actions in the past, present, and future for the harm and eradication of indigenous peoples. This contemporary and ancient darkness is addressed in one of my final poems, “The Exegesis of Jeremy Christian,” centering around a double homicide motivated by racial hatred in my adopted hometown of Portland, Oregon in 2017, a city that has been in the 20th century and now this one a sometimes clandestine, sometimes out loud, northwestern headquarters of the Invisible Empire.

So, at the deepest levels of my ancestry, there are mythic quakes from the stony pantheon of pre-Christian Norse gods; alternative Judaeo-Christian histories; and nearer the surface, craven eugenicist designs of erasure of native peoples by “settling” the American West (and conversion). The last of course isn’t particular to my line, it’s just the unabashed nation-building story of populating an “empty” America. Poetry that will surely outlast my own and might even, rightfully so, render it inert, is being produced by Joy Harjo, Sherwin Bitsui, and many others, against a lineage of oppression and alongside the fractured inheritances of their ancestors. How does a non-native poet come to terms with their past and the shadow it casts over the very reason for their being here at all?

Photo taken of the Oakland Temple (a place my friend Cailie thought was Disneyland as a child growing up in the Bay Area) under a red sky during the SCD Complex Fire between August and September 2020

Final considerations: Mountains and seas

My aim was to have Greco-Mormon stand like a website banner over the amalgamation of my origins: temporal/secular, eternal/religious, matriarchal/patriarchal, life in church/away in school & society. As I get older, geometry and geology, quantum physics, and political philosophy inform a lot more of my work in poetry, and one could use the analogies of layers of sediment or quantum states for the chapbook. The existence upon which the present is built, whether self or nation, only stands because it can do so in a hierarchy of accretion. In this sense, excavations might be more apt descriptor of my verse.

Among the poems of Greco-Mormon are fluctuations in pitch and timber depending on their level: grief, dads, religious violence, paradox, climate change, fertility, and faith. Faith is not a fact, but it is a facet of the lives of people who have shaped and influenced me. In the opening lines of Greco-Mormon, in my poem “The Happy Search,” I distill this with

Faith can move mountains

And so can bulldozers.

These two lines are on their surface a statement about the Holocene and the terror of our earth-shattering Anthropocene, the accumulated mass acts of the industrial reshaping of the surface of Earth, a scale of activity that turns the parable of Jesus into a grim irony. They aren’t against his teaching or the power of faith, but that there are different levels of truth, of ruin, of miraculous occurrences. “And so can” doesn’t nullify the parable but adumbrates it, lining the former image with an absence made by its opposite – brute force.

Temples in the LDS church are called “Mountains of the Lord” and mountains have long been spiritual symbols of the connection between the earth and the heavens. Without the stonemasons of the British Isles, the spires of the Salt Lake Temple would never have risen above a transformed desert landscape. However, the real strength of one’s faith ought not to be anchored in anything material but in consciousness itself, the unseen. A mountain was a fitting multi-layered image to begin the chapbook, and it’s the start of a constant interplay between the heights where I was born (Provo, Utah sits at 4,551 ft above sea level) and the sea to which everything eventually flows, like particles of cremation ash.

I still carry around one strong belief: that successful poetry should speak to you from a deeper level, plucking strings that resonate with acoustic forms behind or beneath our purely sensory-based faculties and culturally informed optics. Poetry that works touches a place where memory and reality mingle, where language can be less opaque and like an agate, more layered and translucent. This belief is based on my own reading, writing, and teaching of poetry. After 35 years of reading, 25 years of writing, and 5 years of teaching poetry, I’m wrestling with myself toward this aim all the time. We might forget that so many science experiments are failures but poetry is no exception. Often enough in both cases, mistakes count and can even produce a different result than hypothesized or expected.

What previous generations of Americans have believed and expected, and especially what Christian Americans of all denominations were or still are proud of, ought to make current generations blush with shame and curdle with righteous horror. How we address, process, and integrate the terrible truths of our lines of blood or adoption is a question that plagues me as the lingering effects of a pandemic virus. I don’t feel I have a choice to deny such an embodied question that exists with my climate grief, pain from the loss of my faith, and dwelling with the sins of my fathers. Has this or does this question lead me to a barren or fertile ground for bringing up poetry? Well, Greco-Mormon by August Janson is one form of an answer.

Greco-Mormon can be published in my Ko-fi store here for $10 (postage included)